First though we had a cup of tea and a chance to inspect Alisdair's latest project, a Caledonian "Jumbo" (294 class 0-6-0 tender loco) from a Worsley Works scratch-aid etch. It looks to be coming together nicely.

The boiler (in the background) is rolled from 4 thou nickel-silver sheet. Alisdair finds brass tube sinks too much heat when soldering in small detail like handrail knobs. 3 thou sheet kinks too easily; 5 thou is too hard to roll smoothly at this diameter (a round file is used as a former: the teeth give enough bite to hold the sheet when starting the curve).

So much for the 2mm boilershop: it was time to go outside to seek out a few reminders of the level of competition between the Caley and North British companies on the north bank of the Clyde. Alisdair was well organised with map and photo handouts, and gave us a mission briefing.

The rest of this blog entry is strictly for bridge-lovers and disused railway junkies. You have been warned! Click on the photos for a more detailed view.

We started out at the former Whiteinch Victoria Park station, the North British terminus of the Whiteinch Railway, a branch of the Stobcross Railway built in the 1870s to get access to the Clyde, and closed to passengers in 1951 and goods in 1965. The station site itself has vanished under an urban park, and there is nothing to see, but the Danes Drive overbridge still stands at the station throat:

We traced the extension from Victoria Park goods yard onwards, down the middle of Scotstoun Street, red sandstone tenements on each side, towards the Clyde, and came to the Caley's 1891 riposte: the Lanarkshire and Dumbartonshire Railway, which linked the Hamiltonhill line bringing traffic from the south-east of the city around its northern circumference before returning south to meet the Clyde at Partick, where it turned west and paralleled the north bank of the river on an embankment to its terminus at Dumbarton, accessing docks and shipyards along the way. This part of the L&D closed in 1966. Scotstoun East station platforms can still be seen here, with the booking office set into the stonework of the bridge:

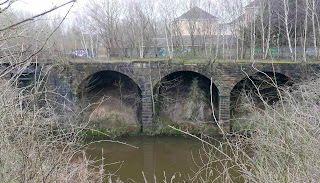

The bridge at Methil Street:

and from rail level:

The island platform (the roadbed is now a cycle and footpath)

Just about the only trace of the station building is the porcelain urinal base of the gentlemen's toilet: Alisdair couldn't resist organising a line-up:

Five minutes and two stations up the line we got out again, at the North British Maryhill station, junction with the Glasgow Dumbarton and Helensburgh Railway which is used by West Highland trains into Queen Street. Both Anniesland and Maryhill stations have long since been replaced by modern brick and metal structures. It started to rain gently, just to remind us we were in Glasgow.

We sought out the nearby River Kelvin, which falls steeply towards the Clyde through north Glasgow, making railway construction here very expensive. The Caley and NB competed to reach every industry alongs its banks and those of the adjoining Forth and Clyde canal. Although the Caley lines were closed in the 1960s, the stone retaining walls and frequent bridge remains still give a powerful sense of just how much capital investment was made here in a few short years at the turn of the nineteenth century, lasting until Glasgow's progressive deindustrialisation and network rationalisation under BR swept most of it away in the 1960s.

First we had a look at the sidings which led to Dalsholm paper mill. This led steeply down from a connection to the NB at Maryhill across the Kelvin on a bridge whose abutments remain visible. Not much to photograph though, so, continuing downstream along the Kelvin Walkway, we passed under the twin viaducts - one stone, one brick - of the GD&H and the Stobcross Railway we'd just used on our short trip from Anniesland. From here on, we were finished with the NB; the rest of the walk would be over former Caley lines.

Wallking onwards, we left the river bank at Cowal Road to get a look at the Forth and Clyde Canal, opened in 1790 to link the east and west coasts of Scotland before the railway age. (From here onwards a map might be helpful: Cowal Road wasn't built until the 1970s, but its predecessor Cowal Street is at the top right of this 1:2500 sheet in the NLS map library).

Maryhill is the site of an impressive ladder of locks and a small graving dock. According to an information panel, barges were built here in the 1940s for use in the Normandy Landings.

The rain was off by now and it was quite warm. We left the canal again and rejoined the north bank of the Kelvin, passing below the massive stone aqueduct.

The aqueduct's stonework is still crisp after well over 200 years.

Alisdair pointed out the almost-illegible painted legend, "PASSENGER STATION", on the aqueduct parapet. This indicated the original footpath to Dawsholm station, opened in the 1890s as northern terminus of the Glasgow Central Railway which tunneled under Glasgow through Central Station Low Level to a sourthern terminus at Rutherglen. In the 1890s Dawsholm was largely in open country with a few industries clustered around the canal, and sizeable gasworks for Glasgow Corporation to the north and west. Perhaps the hope was that housing would develop around the new station. In the event, it was Maryhill, next the NB station and with tramcars to the city centre, which saw its housing expand. Dawsholm remained cut off by its canal and mills until the 1930s when local authority housing grew up on both sides of the Kelvin - far too late for the passenger service, which was withdrawn as early as 1908. Apart from the sign, all other traces of the station have completely disappeared.

As well as the footpath, sidings originally passed under the aqueduct heading upriver to Dawsholm Gasworks, under the bridge carrying Bantaskin Street:

before crossing the Kelvin on a girder bridge whose remaining piers were the vantage point for a mallard duck and drake, unimpressed by our visit.

A further branch led directly from the station yard acrtoss a girder bridge to Temple gasworks near Anniesland where we'd started this part of our journey. The bridge piers showed it had been massively built.

A little further downstream a second bridge from the headshunt led to Kelvindale Paper Works on the other bank, cleared away in the 1970s and now a housing estate.

Back up on the Dawsholm line proper, we inspected the site of Dawsholm engine shed - again, no trace remaining, cleared in the 1960s to build St Gregory's RC church. The Caley had a large six-road shed here with a two-road repair shop which provided motive power for suburban and goods workings linking north and south Glasgow. In the 1960s, BR's four preserved pre-group Scottish steam locos (103, 49, 256, 123) were shedded here to work excursions all over Scotland before final retiral.

A little further on our progress along the Dawsholm line was arrested by the missing viaduct where it crossed the Kelvin to join the Lanarkshire and Dumbartonshire at Bellshaugh Junction. Bellshaugh, Kirklee and Maryhill Junctions formed a triangle here. On the opposite bank. stone viaducts which had supported the yard at Bellshaugh Junction could be seen.

There was just time for a quick look at the surviving viaducts which led tfrom Bellshaugh and Kirklee to Maryhill Central station, now vanished under a supermarket.

Retracing our steps, we crossed the river at Kelvindale Road and got a good view of the remains of the missing Bellshaugh viaduct.

Then we headed back upstream along the other bank of the river, taking a quick detour through a small modern housing development to find the point where the Lanarkshire and Dumbartonshire dives into Balgray tunnel on its way towards Kelvinside station and Partick, just along from Scotstoun East.

Andy's troglodyte instincts started to twitch when he found that the gate at the tunnel entrance had been forced open, but reason prevailed (and the sense that his car parking time back at Anniesland was shortly coming to an end). Picking up the pace a little, we walked back to the Kelvin and followed it upstream until we reached the canal, where we turned westwards along its bank, the Temple gasworks branch now on our left in a cutting. At one time a wharf on the oppiste canal bank was rail-served. We followed the canal back towards Anniesland, then headed along Strathcona Drive, where we had a good view of a recently-installed turnout linking the Stobcross line from Maryhill to the Milngavie line. This heads to the right in this view; the line on the left leads to the bay at Anniesland station from which our diesel unit had set out). This connection was added to facilitate diversions during the recent reconstruction of the Queen Street tunnel.

Knightswood South Junction is the other end of that connection. The catenary on the branch goes no further than this point: it is just long enough to allow trains on the Milngavie line to be turned back at Anniesland if necessary without blocking the main line.

And that was it - after a four-mile walk round this fascinating area, we'd come full circle and there was just time to nip back to Alisdair's for a welcome further cup of tea before heading home.

This was not the typical construction session of an F&C area group meeting, but in fact our walk was full of modelling interest, given the wide variety of bridge designs and stonework textures on view. Well done Alisdair and thank you very much for all that research and preparation ... time well spent, and it helped us work off the lunchtime bacon rolls and cakes. Who said Scottish railways are all about single track passing places in the mirk of a Highland glen?